I grew up in rural Idaho in the late 80s and early 90s. My childhood was idyllic. I’m the oldest of five children. My father was an engineer-turned-physician, and my mother was a musician — she played the violin and piano. We lived in an amazing community, with great schools, dear friends and neighbors. There was lots of skiing, biking, swimming, tennis, and time spent outdoors.

If something was very difficult, I was taught that you just had to reframe it as a small or insignificant moment compared to the vast eternities and infinities around us. It was a Mormon community, and we were a Mormon family, part of generations of Mormons. I can trace my ancestry back to the early Mormon settlers. Our family were very observant: going to church every Sunday, and deeply faithful to the beliefs and tenets of the Mormon Church.

There’s a belief in Mormonism: “As man is, God once was. As God is, man may become.” And since God is perfect, the belief is that we too can one day become perfect.

We believed in perfection. And we were striving to be perfect—realizing that while we couldn’t be perfect in this life, we should always attempt to be. We worked for excellence in everything we did.

It was an inspiring idea to me, but growing up in a world where I felt perfection was always the expectation was also tough.

In a way, I felt like there were two of me. There was this perfect person that I had to play and that everyone loved. And then there was this other part of me that was very disappointed by who I was—frustrated, knowing I wasn’t living up to those same standards. I really felt like two people.

This perfectionism found its way into many of my pursuits. I loved to play the cello. Yo-Yo Ma was my idol. I played quite well and had a fabulous teacher. At 14, I became the principal cellist for our all-state orchestra, and later played in the World Youth Symphony at Interlochen Arts Camp and in a National Honors Orchestra. I was part of a group of kids who were all playing at the highest level. And I was driven. I wanted to be one of the very, very best.

I went on to study at Northwestern in Chicago and played there too. I was the youngest cellist in the studio of Hans Jensen, and was surrounded by these incredible musicians. We played eight hours a day, time filled with practice, orchestra, chamber music, studio, and lessons. I spent hours and hours working through the tiniest movements of the hand, individual shifts, weight, movement, repetition, memory, trying to find perfect intonation, rhythm, and expression. I loved that I could control things, practice, and improve. I could find moments of perfection.

I remember one night being in the practice rooms, walking down the hall, and hearing some of the most beautiful playing I’d ever heard. I peeked in and didn’t recognize the cellist. They were a former student now warming up for an audition with the Chicago Symphony.

Later on, I heard they didn’t get it. I remember thinking, “Oh my goodness, if you can play that well and still not make it…” It kind of shattered my worldview—it really hit me that I would never be the very best. There was so much talent, and I just wasn’t quite there.

I decided to step away from the cello as a profession. I’d play for fun, but not make it my career. I’d explore other interests and passions.

There’s a belief in Mormonism: “As man is, God once was. As God is, man may become.”

As I moved through my twenties, my relationship with Mormonism started to become strained. When you’re suddenly 24, 25, 26 and not married, that’s tough. Brigham Young [the second and longest-serving prophet of the Mormon Church] said that if you’re not married by 30, you’re a menace to society. It just became more and more awkward to be involved. I felt like people were wondering, “What’s wrong with him?”

Eventually, I left the church. And I suddenly felt like a complete person — it was a really profound shift. There weren’t two of me anymore. I didn’t have to put on a front. Now that I didn’t have to worry about being that version of perfect, I could just be me.

But the desire for perfection was impossible for me to kick entirely. I was still excited about striving, and I think a lot of this energy and focus then poured into my work and career as a designer and researcher. I worked at places like the Mayo Clinic, considered by many to be the world’s best hospital. I studied in London at the Royal College of Art, where I received my master’s on the prestigious Design Interactions course exploring emerging technology, futures, and speculative design. I found I loved working with the best, and being around others who were striving for perfection in similar ways. It was thrilling.

One of the big questions I started to explore during my master’s studies in design, and I think in part because I felt this void of meaning after leaving Mormonism, was “what is important to strive for in life?” What should we be perfecting? What is the goal of everything? Or in design terms, “What’s the design intent of everything?”

I spent a huge amount of time with this question, and in the end I came to the conclusion that it’s happiness. Happiness is the goal. We should strive in life for happiness. Happiness is the design intent of everything. It is the idea that no matter what we do, no matter what activity we undertake, we do it because we believe doing it or achieving the thing will make us better off or happier. This fit really well with the beliefs I grew up with, but now I had a new, non-religious way in to explore it.

The question then became: What is happiness? I came to the conclusion that happiness is chemical—an evolved sensation that indicates when our needs in terms of survival have been met. You’re happy when you have a wonderful meal because your body has evolved to identify good food as improving your chances of survival. The same is true for sleep, exercise, sex, family, friendships, meaning, purpose–everything can be seen through this evolutionary happiness lens.

So if happiness evolved as the signal for survival, then I wanted to optimize my survival to optimize that feeling. What would it look like if I optimized the design of my life for happiness? What could I change to feel the most amount of happiness for the longest amount of time? What would life look like if I lived perfectly with this goal in mind?

I started measuring my happiness on a daily basis, and then making changes to my life to see how I might improve it. I took my evolutionary basic needs for survival and organized them in terms of how quickly their absence would kill me as a way to prioritize interventions.

Breathing was first on the list — we can’t last long without it. So I tried to optimize my breathing. I didn’t really know how to breathe or how powerful breathing is—how it changes the way we feel, bringing calm and peace, or energy and alertness. So I practiced breathing.

The optimizations continued, diet, sleep, exercise, material possessions, friends, family, purpose, along with a shedding of any behaviour or activity that I couldn’t see meaningfully improving my happiness. For example, I looked at clothing and fashion, and couldn’t see any real happiness impact. So I got rid of almost all of my clothing, and have worn the same white t-shirts and grey or blue jeans for the past 15 years.

I got involved in the Quantified Self (QS) movement and started tracking my heart rate, blood pressure, diet, sleep, exercise, cognitive speed, happiness, creativity, and feelings of purpose. I liked the data. I’d go to QS meet-ups and conferences with others doing self experiments to optimize different aspects of their lives, from athletic performance, to sleep, to disease symptoms.

I also started to think about longevity. If I was optimizing for happiness through these evolutionary basics, how long could one live if these needs were perfectly satisfied? I started to put on my websites – “copyright 2103”. That’s when I’ll be 125. That felt like a nice goal, and something that I imagined could be completely possible — especially if every aspect of my life was optimized, along with future advancements in science and medicine.

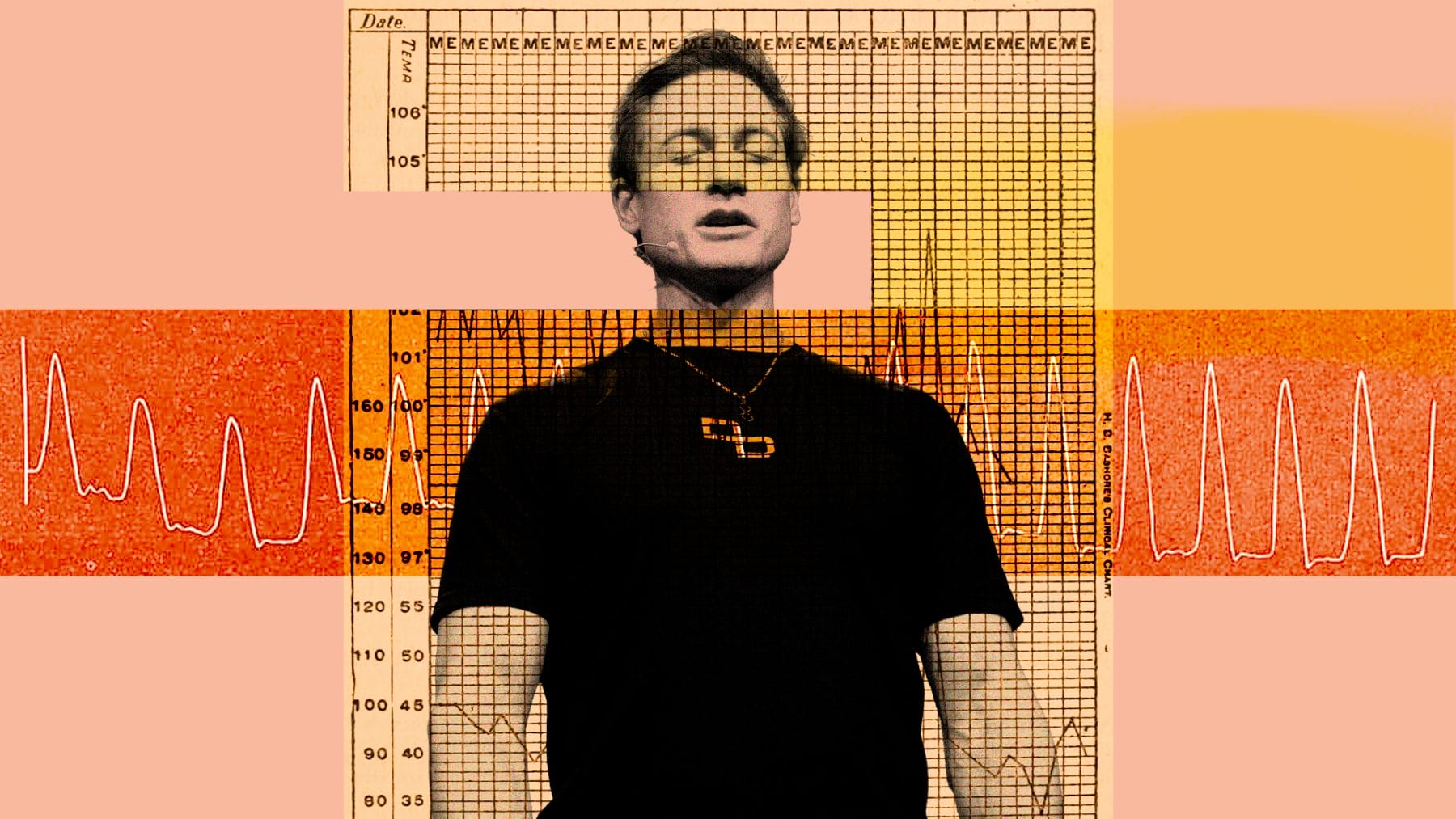

In 2022, some 12 years later, I came across Bryan Johnson. A successful entrepreneur, also ex-Mormon, optimizing his health and longevity through data. It was familiar. He had come to this kind of life optimization in a slightly different way and for different reasons, but I was so excited by what he was doing. I thought, “This is how I’d live if I had unlimited funds.”

He said he was optimizing every organ and body system: What does our heart need? What does our brain need? What does our liver need? He was optimizing the biomarkers for each one. He said he believed in data, honesty and transparency, and following where the data led. He was open to challenging societal norms. He said he had a team of doctors, had reviewed thousands of studies to develop his protocols. He said every calorie had to fight for its life to be in his body. He suggested everything should be third-party tested. He also suggested that in our lifetime advances in medicine would allow people to live radically longer lives, or even to not die.

These ideas all made sense to me. There was also a kind of ideal of perfect and achieving perfection that resonated with me. Early on, Bryan shared his protocols and data online. And a lot of people tried his recipes and workouts, experimenting for themselves. I did too. It also started me thinking again more broadly about how to live better, now with my wife and young family. For me this was personal, but also exciting to think about what a society might look like when we strived at scale for perfection in this way. Bryan seemed to be someone with the means and platform to push this conversation.

I think all of my experience to this point was the set up for, ultimately, my deep disappointment in Bryan Johnson and my frustrating experience as a participant in his BP5000 study.

In early 2024 there was a callout for people to participate in a study to look at how Bryan’s protocols might improve their health and wellbeing. He said he wanted to make it easier to follow his approach, and he started to put together a product line of the same supplements that he used. It was called Blueprint – and the first 5000 people to test it out would be called the Blueprint 5000, or BP5000. We would measure our biomarkers and follow his supplement regime for three months and then measure again to see its effects at a population level. I thought it would be a fun experiment, participating in real citizen science moving from n=1 to n=many. We had to apply, and there was a lot of excitement among those of us who were selected. They were a mix of people who had done a lot of self-quantification, nutritionists, athletes, and others looking to take first steps into better personal health. We each had to pay about $2,000 to participate, covering Blueprint supplements and the blood tests, and we were promised that all the data would be shared and open-sourced at the end of the study.

The study began very quickly, and there were red flags almost immediately around the administration of the study, with product delivery problems, defective product packaging, blood test problems, and confusion among participants about the protocols. There wasn’t even a way to see if participants died during the study, which felt weird for work focused on longevity. But we all kind of rolled with it. We wanted to make it work.

J. Paul took these supplements:

J. Paul and his fellow participants took the following supplements: N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC), Nicotinamide Riboside Chloride (NR), Zeaxanthin, Phosphorus, Astaxanthin (Natural), Boron Glycinate, CaAKG, Ashwagandha KSM66, Calcium L-5-Methyltetrahydrofolate (L-5-MTHF-Ca), Cocoa Powder (Non-Alkalised) 8+% Flavanols, Red Yeast Rice (2% Monacolin K), Creatine Monohydrate, Ginger, Glucosamine Sulfate KCI, Grape Seed Extract 90% polyphenols, Broccoli Extract (glucoraphanin 10%), Glycine, Theanine, Lactobacillus Acidophilus, Lithium orotate, Pomegranate Juice Extract (50% Polyphenols),

Potassium Iodate, Rhodiola 3% Rosavins / Salidroside 1%, Selenium, Glutathione reduced, Lutein, Luteolin, Cinnamon powder (ceylon) organic, Sodium Hyaluronate, Spermidine, Vitamin B1 (Thiamine HCl), Vitamin B12 (Methylcobalamin), Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin-5-Phosphate), Vitamin B3 (Niacinamide), Vitamin B5 (Calcium-D-Pantothenate), Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxal-5-Phosphate), Vitamin B7 (D-Biotin), Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid), Vitamin D Veg D3, Vitamin E (d-alpha tocopherol), Vitamin K1, Vitamin K2 MK-7 MCT Oil, Vitamin K2 MK-4 MCT Oil, Sunflower lecithin non-GMO, Phosphatidylcholine, Choline, Lycopene, Lysine, Taurine, Glucoraphanin, Ubiquinol, Zinc Citrate, Fiber, Blueberries, Macadamia nuts, Walnuts, Omega 3, Omega 6, Calcium, EVOO polyphenols, Oleic acid, Protein (plant), Copper, Caffeine, Magnesium Citrate, Curcuminoids, Fisetin (smoketree extract), Garlic extract 12:1 odorless, Genistein (Japonica extract), Milled Golden Flaxseed, SDG lignan, Phosphatidylinositol, Phosphatidylethanolamine

We took baseline measurements, weighed ourselves, measured body composition, uploaded Whoop or Apple Watch data, did blood tests covering 100s of biomarkers, and completed a number of self-reported studies on things like sexual health and mental health. I loved this type of self-measurement.

Participants connected over Discord, comparing notes, and posting about our progress.

Right off, some effects were incredible. I had a huge amount of energy. I was bounding up the stairs, doing extra pull-ups without feeling tired. My joints felt smooth. I noticed I was feeling bulkier — I had more muscle definition as my body fat percentage started to drop.

There were also some strange effects. For instance, I noticed in a cold shower, I could feel the cold, but I didn’t feel any urgency to get out. Same with the sauna. I had weird sensations of deep focus and vibrant, vivid vision. I started having questions—was this better? Had I deadened sensitivity to pain? What exactly was happening here?

Then things went really wrong. My ears started ringing — high-pitched and constant. I developed Tinnitus. And my sleep got wrecked. I started waking up at two, three, four AM, completely wired, unable to turn off my mind. It was so bad I had to stop all of the Blueprint supplements after only a few weeks.

On the Discord channel where we were sharing our results, I saw Bryan talking positively about people having great experiences with the stack. But when I or anyone else mentioned adverse side effects, the response tended to be: “wait until the study is finished and see if there’s a statistical effect to worry about.”

So positive anecdotes were fine, but when it came to negative ones, suddenly, we needed large-scale data. That really put me off. I thought the whole point was to test efficacy and safety in a data-driven way. And the side effects were not ignorable.

Many of us were trying to help each other figure out what interventions in the stack were driving different side effects, but we were never given the “1,000+ scientific studies” that Blueprint was supposedly built upon which would have had side-effect reporting. We struggled even to get a complete list of the interventions that were in the stack from the Blueprint team, with numbers evolving from 67 to 74 over the course of the study. It was impossible to tell which ingredient in which products was doing what to people.

We were told to no longer discuss side-effects in the Discord but email Support with issues. I was even kicked off the Discord at one point for “fear mongering” because I was encouraging people to share the side effects they were experiencing.

The Blueprint team were also making changes to the products mid-study, changing protein sources and allulose levels, leaving people with months’ worth of expensive essentially defective products, and surely impacting study results.

When Bryan then announced they were launching the BP10000, allowing more people to buy his products, even before the BP5000 study had finished, and without addressing all of the concerns about side effects, it suddenly became clear to me and many others that we had just been part of a launch and distribution plan for a new supplement line, not participants in a scientific study.

Bryan has not still to this day, a year later, released the full BP5000 data set to the participants as he promised to do. In fact he has ghosted participants and refuses to answer questions about the BP5000. He blocked me on X recently for bringing it up. I suspect that this is because the data is really bad, and my worries line up with reporting from the New York Times where leaked internal Blueprint data suggests many of the BP5000 participants experienced some negative side effects, with some participants even having serious drops in testosterone or becoming pre-diabetic.

I’m still angry today about how this all went down. I’m angry that I was taken in by someone I now feel was a snake oil salesman. I’m angry that the marketing needs of Bryan’s supplement business and his need to control his image overshadowed the opportunity to generate some real science. I’m angry that Blueprint may be hurting some people. I’m angry because the way Bryan Johnson has gone about this grates on my sense of perfection.

Bryan’s call to “Don’t Die” now rings in my ears as “Don’t Lie” every time I hear it. I hope the societal mechanisms for truth will be able to help him make a course correction. I hope he will release the BP5000 data set and apologize to participants. But Bryan Johnson feels to me like an unstoppable marketing force at this point — full A-list influencer status — and sort of untouchable, with no use for those of us interested in the science and data.

This experience has also had me reflecting on and asking bigger questions of the longevity movement and myself.

We’re ignoring climate breakdown. The latest indications suggest we’re headed toward three degrees of warming. These are societal collapse numbers, in the next 15 years. When there are no bees and no food, catastrophic fires and floods, your Heart Rate Variability doesn’t really matter. There’s a sort of “bunker mentality” prevalent in some of the longevity movement, and wider tech — we can just ignore it, and we’ll magically come out on the other side, sleep scores intact.

The question then became: What is happiness? I came to the conclusion that happiness is chemical—an evolved sensation that indicates when our needs in terms of survival have been met.

I’ve also started to think that calls to live forever are perhaps misplaced, and that in fact we have evolved to die. Death is a good thing. A feature, not a bug. It allows for new life—we need children, young people, new minds who can understand this context and move us forward. I worry that older minds are locked into outdated patterns of thinking, mindsets trained in and for a world that no longer exists, thinking that destroyed everything in the first place, and which is now actually detrimental to progress. The life cycle—bringing in new generations with new thinking—is the mechanism our species has evolved to function within. Survival is and should be optimized for the species, not the individual.

Bryan Johnson response

When we reached out to Bryan Johnson about J Paul’s concerns, we received the following response:

“It was a study. The results were shared with the participants. We take all feedback seriously.

Participants voluntarily took the Blueprint stack for 90 days and monitored their health metrics.* They were encouraged to continue their existing daily routines during this period. We compared their measurements before the 90 days began at the 90-day mark.**

This study was conducted to assess the effect of the Blueprint Stack on the overall health of the participants. The results and statements in this study have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

After 90 days, we saw the following statistically significant results among participants:

Improved depression symptoms by 23%

Improved anxiety symptoms by 26%

Improved blood pressure by 7%

Improved sleep quality by 3.9%

Improved time-to-sleep by 5 minutes

Improved musculoskeletal health by 2.6%

Normalized kidney dysfunction for 25.6%

Normalized heart dysfunction for 17.1%

Normalized elevated cholesterol levels

Normalized DNA repair dysfunction for 20%

Normalized liver dysfunction for 13.6%

Normalized elevated inflammation for 11.5%

I love thinking about the future. I love spending time there, understanding what it might look like. It is a huge part of my design practice. But as much as I love the future, the most exciting thing to me is the choices we make right now in each moment. All of that information from our future imaginings should come back to help inform current decision-making and optimize the choices we have now. But I don’t see this happening today. Our current actions as a society seem totally disconnected from any optimized, survivable future. We’re not learning from the future. We’re not acting for the future.

We must engage with all outcomes, positive and negative. We’re seeing breakthroughs in many domains happening at an exponential rate, especially in AI. But, at the same time, I see job displacement, huge concentration of wealth, and political systems that don’t seem capable of regulating or facilitating democratic conversations about these changes. Creators must own it all. If you build AI, take responsibility for the lost job, and create mechanisms to share wealth. If you build a company around longevity and make promises to people about openness and transparency, you have to engage with all the positive outcomes and negative side effects, no matter what they are.

I’m sometimes overwhelmed by our current state. My striving for perfection and optimizations throughout my life have maybe been a way to give me a sense of control in a world where at a macro scale I don’t actually have much power. We are in a moment now where a handful of individuals and companies will get to decide what’s next. A few governments might be able to influence those decisions. Influencers wield enormous power. But most of us will just be subject to and participants in all that happens. And then we’ll die.

But until then my ears are still ringing.

This article was put together based on interviews J.Paul Neeley did with Isobel Cockerell and Christopher Wylie, as part of their reporting for CAPTURED, our new audio series on how Silicon Valley’s AI prophets are choosing our future for us. You can listen now on Audible.